Animals don’t behave for the good of the species. They behave to maximize the number of copies of their genes passed into the next generation.

The extent to which a male primate cares for infants reflects his certainty of paternity. Among marmosets, who form stable pair-bonds, males do most of the child care. In contrast, among baboons, where a female mates with multiple males during her estrus cycle, it’s only the likely fathers who invest in the well-being of the child, aiding him in a flight.

The most visible proponent of the gene-centered view has long been Dawkins, with his iconic ‘selfish gene’ meme – it is the gene that is passed to the next generation, the thing whose variants spread or decline over time. Moreover, a gene is a clear and distinctive sequence of letters, reductive and irrefutable, while phenotypic traits are much fuzzier and less distinct.

The organism is just a vehicle for the genome to be replicated in the next generation, and behavior is just this wispy epiphenomenon that facilitates the replication.

Can’t we all get along? There’s the obvious bleeding-heart answer, namely that there’s room for a range of views and mechanisms in our rainbow-colored tent of evolutionary diversity. Different circumstances bring different levels of selection to the forefront. Sometimes the most informative level is the single gene, sometimes the genomes, sometimes a single phenotypic trait, sometimes the collection of all the organism’s phenotypic traits. We’ve just arrived at the reasonable idea of multilevel selection.

…. This is a world away from “animals behave for the good of the species.” Instead, this is the circumstance of a genetically influenced trait that, while adaptive on an individual level, emerges as maladaptive when shared by a group and where there is competition between groups (e.g., for an ecological niche).

Our three-legged chair of individual selection, kin selection, and reciprocal altruism seems more stable with four legs.

Pharaoh Ramses II, incongruously now associated with a brand of condoms, had 160 children and probably couldn’t tell any of them from Moses. Within half a century of his death in 1953, Ibn Saud, the founder of the Saudi dynasty, had more than three thousand descendants. Genetic studies suggest that around sixteen million people today are descended from Genghis Khan.

Who feels like a relative (and thus not like a potential mate)? Someone with whom you took a lot of baths when you both were kids.

Human irrationality in distinguishing kin from nonkin takes us to the heart of our best and worst behaviors. This is because of something crucial – we can be manipulated into feeling more or less related to someone than we actually are.

Rules, laws, treaties, penalties, social conscience, an inner voice, morals, ethics, divine retribution, kindergarten songs about sharing – all driven by the third leg of the evolution of behavior, namely that it is evolutionarily advantageous for nonrelatives to cooperate. Sometimes.

So humans excel at cooperation among nonrelatives. We’ve already considered circumstances that favor reciprocal altruism; this will be returned to in the final chapter. Moreover, it’s not just groups of nice chickens outcompeting groups of mean ones that has revivified group selectionism. It is at the core of cooperation and competition among human groups and cultures.

This next challenge addresses whether evolution is actually more about rapid evolution than about slow reform. Evolutionary bottleneck?

Gradual evolution – kinda creepy, as every slight advantage counts

Punctuated equilibrium – some jerks change the genes of a species all of sudden

Thus, both gradualism and punctuated change occur in evolution, probably depending upon the genes involved – for example, there has been faster evolution of genes expressed in some brain regions than others. And no matter how rapid the changes, there’s always some degree of gradualism – no female has given birth to a member of a new species.

The problem was that sociobiology explained too much and predicted too little.

Evolution is a tinker, not an inventor.

The critics used the “is versus ought” contrast, saying, “Sociobiologists imply that when an unfair feature of life is the case, it is because it ought to be.” And the sociobiologists responded by flipping is/ought around: “We agree that life ought to be fair, but nonetheless, this is reality. Saying that we advocate something just because we report it is like saying oncologists advocate cancer.”

While sociobiology may explain too much and predict too little, it does predict many broad features of behavior and social systems across species.

The context and meaning of a behavior are usually more interesting and complex than the mechanics of the behavior.

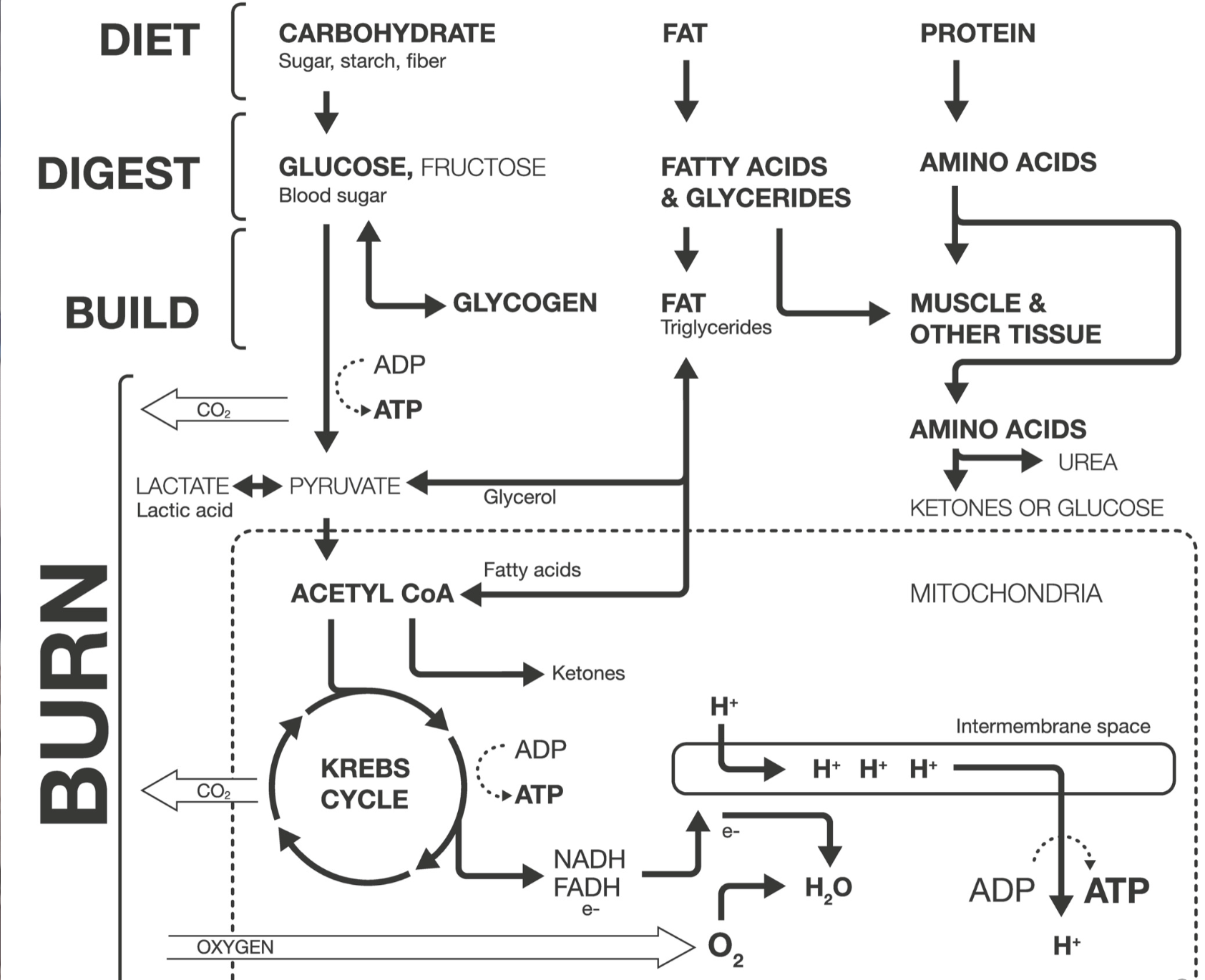

To understand things, you mush incorporate neurons and hormones and early development and genes, etc., etc.

These aren’t separate categories – there are few clear-cut causal agents, so don’t count on there being the brain region, the neurotransmitter, the gene, the cultural influence, or the single anything that explains a behavior.

Instead of causes, biology is repeatedly about propensities, protentials, vulnerabilities, predispositions, proclivities, interactions, modulations, contingencies, if/then clauses, context dependencies, exacerbation or diminution of preexisting tendencies. Circles and loops and spirals and Mobius strips.

No one said this was easy. But the subject matters.

Specifically, people with the strongest negative toward immigrants, foreigners, and socially deviant groups tend to have low thresholds for interpersonal disgust (e.g. are resistant to wearing a stranger’s clothes or sitting in a warm seat just vacated).