by Siddhartha Mukherjee

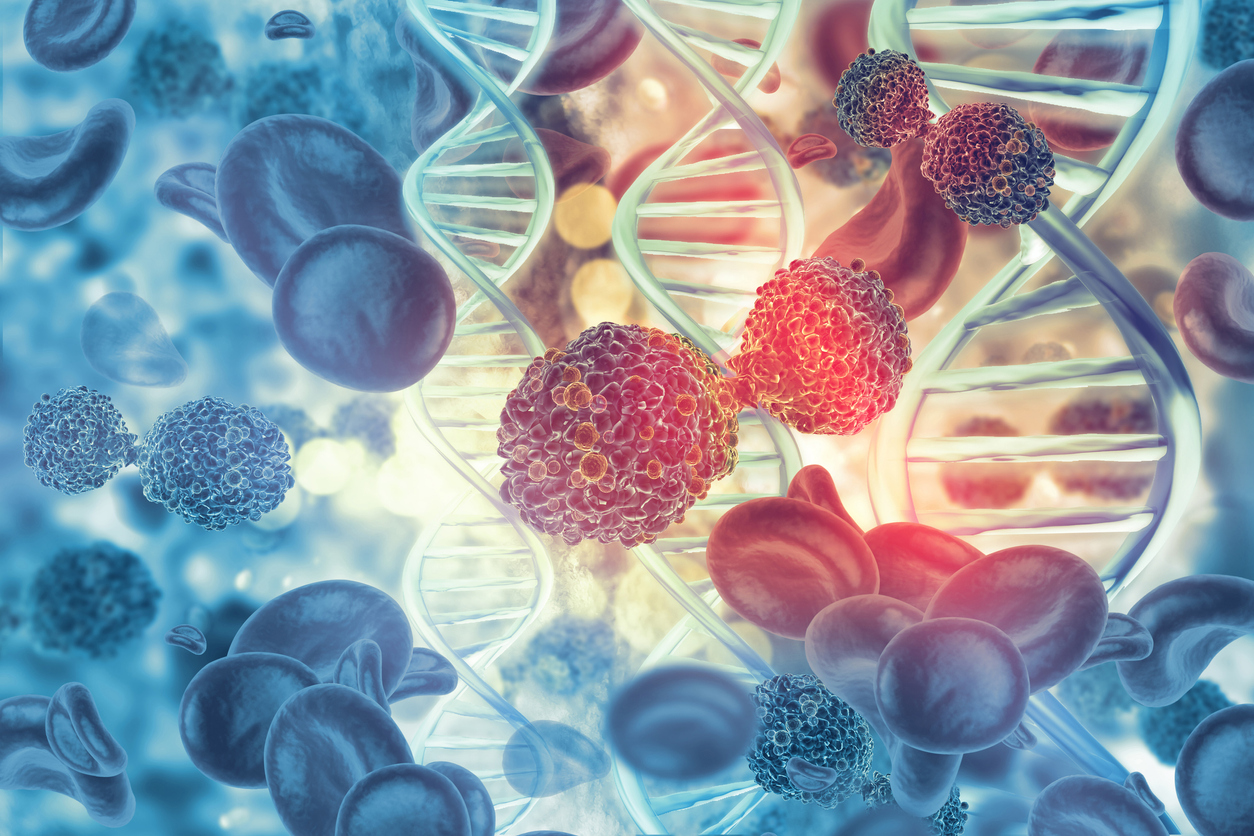

As Susan Sontag strongly argued in Illness as Metaphor, cancer is a quintessential twentieth-century disease, much like tuberculosis was seen as a defining illness of the nineteenth century. Sontag pointed out that both diseases were perceived as “unclean”—not just metaphorically but in the literal sense of being ominous, malignant, and physically repulsive. Both drain the body’s vitality and lead to prolonged suffering rather than immediate death. In both cases, the experience of dying is more emblematic of the disease than death itself.

In the nineteenth century, doctors often linked cancer to civilization, believing that the chaos and pace of modern life somehow triggered pathological changes in the body, leading to cancer. While this reasoning was not entirely wrong, it did not establish causation. Civilization did not cause cancer; rather, by extending human life, it simply exposed it.

Radiation therapy propelled cancer medicine into an era filled with both hope and peril—an atomic age in every sense. The language, imagery, and metaphors surrounding treatment reflected this atomic force, striking directly at cancer with words like cyclotron, high-voltage radiation, linear accelerator, and neutron beam. Patients were sometimes told to imagine X-ray therapy as being hit by the energy of a million microscopic bullets. Others described radiation treatment as eerie and terrifying, almost like space travel: The patient is placed on a stretcher inside an oxygen chamber. A six-member medical team—doctors, nurses, and technicians—moves swiftly around them. The radiologist positions the electronic induction accelerator. After sealing the oxygen chamber with a resounding clang, technicians pressurize it with oxygen. Once full pressure is maintained for 15 minutes, the radiologist activates the accelerator, directing radiation at the tumor. When treatment is complete, the patient undergoes decompression in a deep-sea diving mode before being transferred to the recovery room.

Cancer treatment stands at a complex crossroads. Sometimes, radiation therapy cures cancer; other times, it causes it. This sobering reality doused the initial enthusiasm of cancer researchers with cold water. Radiation, though an invisible and precise blade, remains a blade nonetheless. No matter how skillful or sharp, it has reached its limits in the war against cancer. A more discerning approach is needed—especially for metastatic cancer.

In truth, Galen may have been right after all—just as Democritus once stumbled upon his atomic theories by intuition, or as Erasmus speculated about the Big Bang centuries before galaxies were discovered. Of course, Galen misunderstood the true cause of cancer—there is no black bile bubbling chaotically within the body to form tumors. Yet, with an almost dreamlike, instinctive analogy, he managed to capture a fundamental truth about cancer. It behaves like a disease of the fluids, moving through the body like a crab, spreading in all directions. It travels unseen through pathways, burrowing from one organ to another. As Galen understood it, cancer is a systemic disease.

“Life is… a chemical event.” — Paul Ehrlich, written during his student years in 1870.

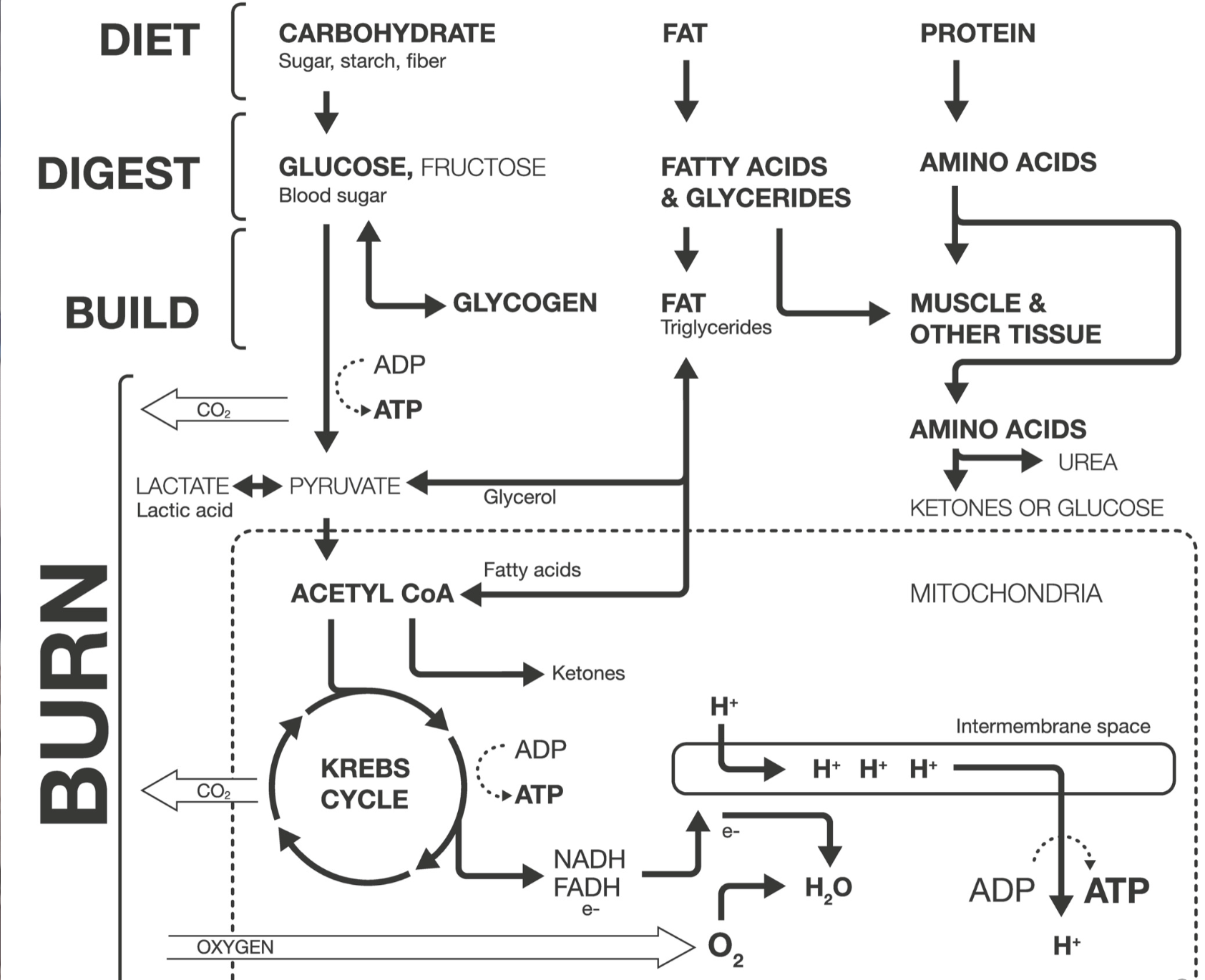

In 1828, the Berlin scientist Friedrich Wöhler triggered an upheaval in the scientific world by creating a supernatural storm of discovery. By boiling ammonium cyanate—an ordinary inorganic salt—he synthesized urea, a substance previously believed to be produced only by the kidneys. Wöhler’s experiment, seemingly simple, carried profound implications. Urea was considered a natural chemical, yet its precursor was an inorganic salt. A chemical produced by living organisms could now be effortlessly synthesized in a laboratory flask. This shattered the long-held belief that biological chemistry contained some vital force that was beyond replication. For centuries, people assumed that the chemical reactions occurring within living organisms had a mysterious, unreplicable essence—an idea known as vitalism. But Wöhler’s experiment dismantled this theory in an instant, proving that organic and inorganic matter were interchangeable. Biology, at its core, was chemistry. It even suggested that the human body itself was no different from a volatile beaker of reacting chemicals—except that this beaker had arms, legs, eyes, a brain, and perhaps, a soul.

“一如苏珊·桑塔格在《疾病的隐喻》一书中所强烈主张的:癌症是一种“典型的属于20世纪的苦难”,这种观念使人联想起另一种同样被认为是“一个时代的象征”的疾病——肆虐于19世纪的肺结核。桑塔格强调指出,这两种病都相似地“污秽”,“这是从词的本义上来说的——不吉、恶劣、令人感官上厌恶”。两者都会耗干生命力,都令患者迁延致死;在这两种病症中,“濒死”要比“死亡”更能体现疾病的本质。”

“19世纪的医生往往把癌症与文明联系在一起,认为现代生活的匆忙无序在某种程度上刺激了体内的病理变化,导致了癌症。这种推论是正确的,但并不构成因果关系——文明并没有导致癌症,而是通过延长人类的寿命,暴露了癌症。”

“放射治疗把癌症医学推进到了一个载满期望和危险的原子时代。当然,人们所使用的词汇、图像和隐喻都带有原子力量直扑癌症的强烈象征。如“粒子回旋加速器”、“超高压辐射”、“线性加速器”、“中子束”。有人曾被要求将X射线治疗想象成“被上百万个微小子弹的能量击中”。另有人认为放射线治疗充满了惊悚与恐惧,仿佛太空旅行一般:“病人被安置在氧气舱内的担架上。由医生、护士和技术人员六人组成的医疗小组在一旁穿梭忙碌。放射科医生调整电子感应加速器就位;将氧气舱的门砰然关闭之后,技术人员向里面加压注氧;保持满压15分钟后……放射科医生打开电子感应加速器,对肿瘤进行辐射,治疗完毕,再用深海潜水模式给患者减压,然后送往康复室。”

“对于癌症的治疗来说,放射疗法处于复杂的十字路口:有时,放疗可以治癌,有时又会致癌,这无疑给癌症科学家最初的狂热泼了一盆冷水。尽管辐射是一把无形的利刃,但它仍然是一把刀。而这把刀,无论多么灵巧和犀利,在抗癌的战争中也仅能止步于此了。人们需要一个更具分辨力的治疗方法,特别是针对转移性癌症。”

“事实上,可能盖伦终究还是正确的,就像德谟克利特(Democritus)偶然间得出的关于原子的警句,抑或像在人们发现星系之前的几百年,伊拉斯谟(Erasmus)就做出了关于宇宙大爆炸的猜想一样。当然,盖伦错认了癌症真正的起因——并没有什么“黑色的胆汁”塞满身体并在混乱中起泡形成肿瘤。但他以其梦幻、本能的比拟说法,奇迹般地描述了癌症的某些本质。癌症往往是一种体液疾病,它像螃蟹一般横行霸道,并且四处流动。它可以经由无形的通道,从一个器官钻进另一个器官。正如盖伦所理解的那样,癌症是一种系统性疾病。”

“生命是……一场化学事件。——保罗·埃尔利希(Paul Ehrlich)写于1870年的学生时代”

“1828年,柏林科学家弗里德里希·沃勒(Friedrich Whler)发动了一场超自然的科学风暴,他通过煮沸普通的无机盐氰酸铵合成出原本由肾脏才能产生出的尿素。沃勒的实验看似平常,却有着举足轻重的意义。尿素是一种“天然的化学物质”,但沃勒的尿素前身却是无机盐。“一种由天然物质产生的化学物质可以在烧瓶中轻易地衍生出来”,这简直就颠覆了对生物体的全部观念:几个世纪以来,人们认为生物体内的化学反应都带有某些神秘特质,一种无法在实验室复制的活力本质。这一理论被称为“活力论”。但沃勒的实验一举击碎了活力论,证明有机物和无机物之间可以相互转化,生物学即是化学。甚至可能人体与一团激烈反应的化学物质没有差别,不过是有胳膊、腿、眼睛、头脑和灵魂的烧杯。”