Sep 16, 2023

Question: With advances in technology and the advent of neuroimaging techniques, we are able to directly study the brain. Does this mean we no longer need to use animals in our pursuit of understanding human behavior?

Well, not necessarily. Neuroimaging techniques have undoubtedly propelled psychological research forward. Compared to lesion studies, they offer more reliability, and compared to some invasive methods, their side effects are minimal. However, there are still significant limitations. Take fMRI, for instance—while widely used, it must balance temporal and spatial resolution due to the slow nature of the hemodynamic response function.

Beyond that, animal studies offer something neuroimaging alone cannot: greater control over variables. Scientists can regulate the genetic makeup and environmental conditions of animal subjects—though this does not make two rats identical, it allows for far greater consistency than human studies, even among twins. This level of control makes it easier to establish causal relationships in research. Moreover, certain invasive methods, which would be unethical in human research, can still provide critical insights when applied to animals.

Of course, ethical concerns surrounding animal experimentation are complex and deeply personal. Some argue that using animals in research—provided they are not subjected to unnecessary suffering—is justified by the potential benefits to human health and scientific progress. But this perspective inevitably raises difficult questions.

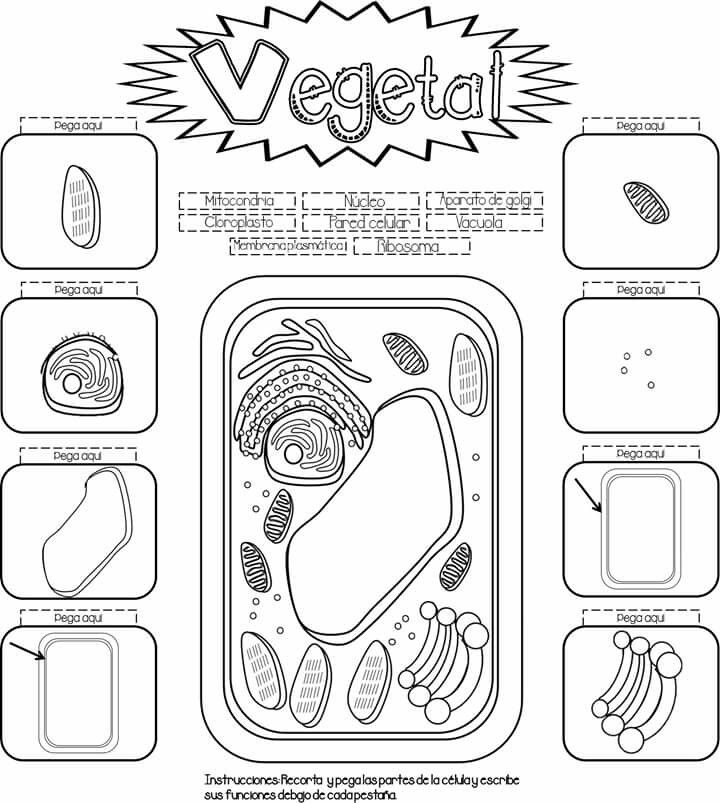

What truly distinguishes humans from other animals? Is intelligence alone enough to grant us dominion over their lives? If we reject that premise, then what separates animals from plants? Does a lack of sentience justify their consumption by herbivores? And if we extend this line of thinking further, what separates our own cells from ourselves? Just because we are conscious, intelligent, and reproduce in a particular way, does that make it justifiable—even inevitable—that we control and destroy other forms of life or non-life, often without even noticing?

This is not to dismiss critiques of anthropocentrism; in fact, we should constantly question how much of our worldview is shaped by it. But perhaps it is also worth acknowledging that, whether we like it or not, we are all complicit in this cycle of life and death. We kill insects in our daily lives, we shed and destroy countless cells within our own bodies every second, and we consume other living things to sustain ourselves. Life is, in some ways, an ongoing paradox—both miraculous and cruel.

Recognizing this does not mean we must abandon ethical consideration. On the contrary, it reminds us that morality exists in tension: between the abstract and the immediate, between long-term benefit and present suffering. Justifying animal experimentation purely through the “greater good” can sometimes feel too detached, too clinical. But at the same time, outright rejection of its role in science would ignore the reality of how much we owe to it.

Perhaps the challenge, then, is not simply to accept or reject animal research, but to approach it with awareness and humility—to hold both abstract, far-reaching love and concrete, immediate compassion in equal regard. Only by doing so can we truly navigate this world—one that is, at once, both beautiful and brutal.

Edited in 2025: Author wrote the answer years ago. Her opinion might have changed.