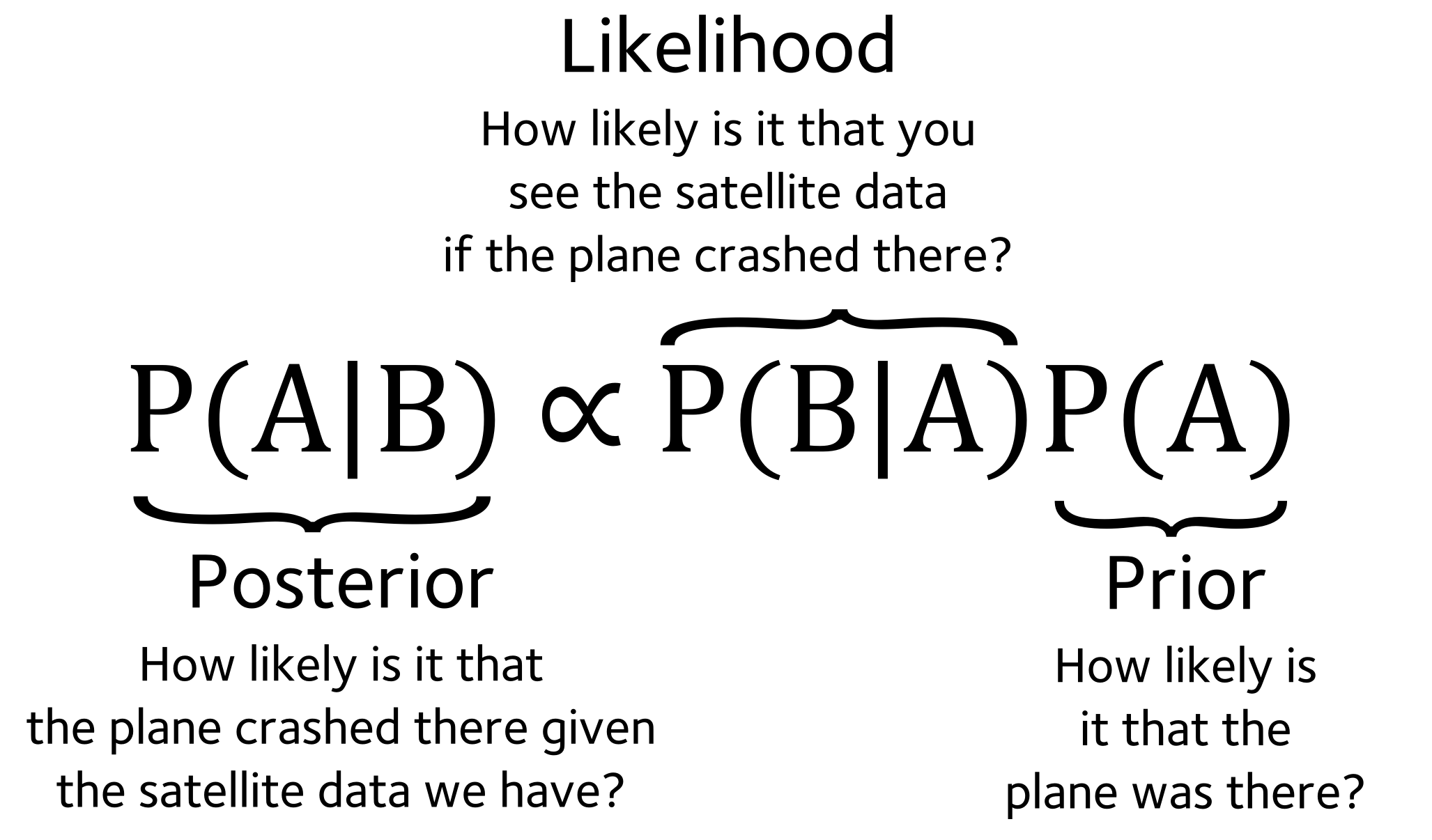

At the heart of Bayesian inference lies a deceptively simple idea: we update our beliefs—our priors—by incorporating new evidence through the likelihood, yielding a revised belief—the posterior. And then we do it all over again. And again. Until what started as a potentially biased assumption becomes something a bit wiser, a bit more refined… kind of like your opinions after arguing with a very persuasive friend.

Bias, in this framework, isn’t a flaw. it’s the starting point. For human beings, reason isn’t a tool to eliminate bias entirely (good luck with that), but rather a way to treat bias as an adjustable parameter. Every time we encounter a new idea, a disagreement, or even an awkward Thanksgiving debate, our initial assumptions are put to the test. If we truly want our beliefs to inch closer to truth, we need to run our internal algorithm: reflect, iterate, and incorporate new data.

It is also essential to recognize that, in most circumstances, what we express – and hear— are opinions. And opinions, by nature, are steeped in bias. Not out of malice, but because they’re born in context. And we, dear reader, are inescapably, products of context. Recognizing both our own limitations and those of others is the first step toward intellectual humility. The next step? Cultivate curiosity. Stay open to the unfamiliar. Invite the unknown in for tea. And do it consistently.

This process is, in fact, what distinguishes scientific institutions from many religious ones. As expressed in the Nexus series, science differs in its ability to revise its doctrines in light of new evidence. It progresses not by clinging to certainty, but by relinquishing outdated convictions, often, as the saying goes, one funeral at a time.

In 1934, Karl Popper proposed that every scientific theory must be falsifiable. Since then, falsifiability has become a central criterion in modern scientific thought. However, from a Bayesian point of view, falsification is itself a probabilistic event. This implies that truth is not a fixed, absolute entity, but rather a distribution of beliefs that are continuously updated as new evidence is introduced.

As the physicist Richard Feynman once said,

“I can live with doubt and uncertainty and not knowing. I think it is much more interesting to live not knowing than to have answers that might be wrong. If we will only allow that, as we progress, we remain unsure, we will leave opportunities for alternatives. We will not become enthusiastic for the fact, the knowledge, the absolute truth of the day, but remain always uncertain … In order to make progress, one must leave the door to the unknown ajar.”

Progress doesn’t come from locking the door on uncertainty. It comes from leaving it just slightly ajar.